Delaware Coast Press, Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, 13 April 2011Delaware diaryWhipping of prisoners was family affairBy Michael Morgan

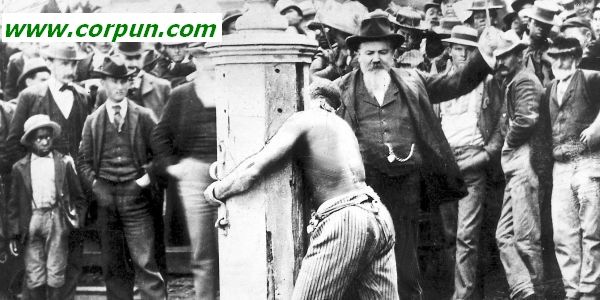

For many southern Delaware families, it was an event that was not to be missed; and on a cold winter morning, residents from across Sussex County swarmed into Georgetown. On Feb. 19, 1932, the Delaware Coast News reported, "More than two thousand people, men, women, and children, some of the women with babies in their arms, stood crowded about the wire enclosure surrounding the new Sussex County Jail...in a chilly February wind, waiting from 10 o'clock until 1:30 to see 5 prisoners whipped." When English colonists arrived in southern Delaware during the 17th century, they brought with them an attitude toward criminals that had its roots in the dark corners of the Middle Ages. After the colonists built a courthouse, they set up a whipping post and began flogging law-breakers into model citizens. When John Johnson sang a "scurrilous, disgraceful song" that Samuel Gray found objectionable, the Sussex County court ordered that Johnson be fined, "five hundred pounds of tobacco or whipped twenty-one lashes on the naked back." It is not known whether Johnson paid the fine or suffered the flogging; but such physical punishments were common in colonial Sussex County. At that time, jails were temporary holding places for those awaiting trials. Instead of incarceration, criminals were sentenced to a variety of corporal penalties that included whipping, branding, lopping off the ears, and in the most severe cases, they could be drawn and quartered, meaning each leg and arm would be attached to horses who would pull in four directions. After the American Revolution, the county courthouse was moved to Georgetown, and a new whipping post and a set of stocks were built so that sentences could be carried out swiftly. Although most states abandoned corporal punishment of criminals, the hipping post remained an entrenched feature of the Delaware legal system. In the years following the Civil War, some Delaware residents began to question the wisdom of flogging criminals. April 21, 1869, the New York Times, quoting a Wilmington newspaper, reported: "The semi-annual barbarities in this state commenced mildly this year, with the flogging of a single colored man, named Joseph Godfrey, at Georgetown, today, he having been convicted of petty larceny at the present term of Court in Sussex County. He receives twenty lashes, is to be imprisoned for six months and wear a convict's jacket six months thereafter. The disgusting exhibition will probably be repeated on a larger scale at Georgetown next Saturday, and then it will work its way up through Kent to New Castle, where in May, more backs will shrink beneath the cruel lash, to the destruction of manhood and the shame of the state." Four years later, the Times published a longer examination of the use of the whipping post: "Corporal punishment is an important feature of the Delaware penal code. For instance, whipping is a part of the punishment of all minor degrees of murder, and for burglary, mayhem, violent assault, kidnapping, highway robbery, attempted poisoning, arson, larceny, counterfeiting, and other felonies and misdemeanors." The number of lashes administered ranged from 20 to 60; and, in general, the whipped person also had to spend an hour in the pillory. Forgery, perjury, fortune-telling, conspiracy, and other offenses were punishable only by a stay in the pillory. By the beginning of the 20th century, support for the whipping post began to wane, and floggings became rare. In 1932, when the five men were whipped at Georgetown, it was an event so rare that families braved the cold wind and weather to witness what may have been the last flogging in Sussex County. The last flogging in Delaware occurred in 1952; and the practice that had crowds of families including babies in arms was formally abandoned 20 years later. Michael Morgan taught high school history for 32 years and holds a master's degree in history from Morgan State University. Sources: • Delaware Coast News, Feb. 19, 1932. The Chronicle Review [The Chronicle of Higher Education], Washington DC, 24 April 2011In Defense of FloggingBy Peter Moskos

A crazy idea came from a dinner in New Orleans. I had cold-called (or whatever the e-mail equivalent is) a writer and his wife because I was a fan of his work and thought we had much in common. They were gracious enough to arrange a meal and treat me, without much justification, as a professional equal more than a stalker. The conversation turned to corporal punishment in public schools. They were amazed not that such a peculiarity existed in a city ripe with oddities, but that such illegal punishments were administered at the urging of and with the full consent of the students' parents. "Fascinating," I drolly replied, but I wasn't shocked. If I'd learned one thing as a police officer patrolling a poor neighborhood, it was the working- and lower-class populations' great fondness for corporal punishment. No punishment is as easy or seemingly satisfying as a physical beating. I learned this not because I beat people, but because the good citizens I swore to serve and protect often urged me to do so. It wasn't hard for me to resist (I liked my job, and besides, I wasn't raised that way), but I agreed that many of the disrespectful hoodlums deserved a beating. Why? Because, as the old-school thinking goes, when people do wrong, they deserve to be punished. For most of the past two centuries, at least in so-called civilized societies, the ideal of punishment has been replaced by the hope of rehabilitation. The American penitentiary system was invented to replace punishment with "cure." Prisons were built around the noble ideas of rehabilitation. In society, at least in liberal society, we're supposed to be above punishment, as if punishment were somehow beneath us. The fact that prisons proved both inhumane and miserably ineffective did little to deter the utopian enthusiasm of those reformers who wished to abolish punishment. Incarceration, for adults as well as children, does little but make people more criminal. Alas, so successful were the "progressive" reformers of the past two centuries that today we don't have a system designed for punishment. Certainly released prisoners need help with life -- jobs, housing, health care -- but what they don't need is a failed concept of "rehabilitation." Prisons today have all but abandoned rehabilitative ideals -- which isn't such a bad thing if one sees the notion as nothing more than paternalistic hogwash. All that is left is punishment, and we certainly could punish in a way that is much cheaper, honest, and even more humane. We could flog. Over that New Orleans dinner, as the wine bottles emptied, somebody ruminated, "with consent of the flogged." I said, "in defense of flogging." We paused. If nothing else, all of us agreed it was a hell of a title! Back home, I mentioned "in defense of flogging" to my editor and his eyes lit up. He told me in no uncertain terms that he was going to publish a book by that name, and I was going to write it. This was 2007, still more than a year before the publication of my first book. And while most young academics would love to have a second book project before they finished their first, I had one great fear: the title. Could it not be Why Prison? or even In Defense of Flogging? But my editor stuck to his guns (and noted that question marks in titles were bad form). When I started writing In Defense of Flogging, I wasn't yet persuaded as to the book's basic premise. I, too, was opposed to flogging. It is barbaric, retrograde, and ugly. But as I researched, wrote, and thought, I convinced myself of the moral justness of my defense. Still, I dared not utter the four words in professional company until after I earned tenure. Is not publishing a provocatively titled intellectual book what academic freedom is all about? Certainly In Defense of Flogging is more about the horrors of our prison-industrial complex than an ode to flogging. But I do defend flogging as the best way to jump-start the prison debate and reach beyond the liberal choir. Generally those who wish to lessen the suffering of prisoners get too readily dismissed as bleeding hearts or soft on criminals. All the while, the public's legitimate demand for punishment has created, because we lack alternatives, the biggest prison boom in the history of the world. Prison reformers -- the same movement, it should be noted, that brought us prisons in the first place -- have preached with barely controlled anger and rational passion about the horrors of incarceration. And to what end? Something needs to change. Certainly my defense of flogging is more thought experiment than policy proposal. I do not expect to see flogging reinstated any time soon. And deep down, I wouldn't want to see it. And yet, in the course of writing what is, at its core, a quaintly retro abolish-prison book, I've come to see the benefits of wrapping a liberal argument in a conservative facade. If the notion of tying people to a rack and caning them on their behinds à la Singapore disturbs you, if it takes contemplating whipping to wake you up and to see prison for what it is, so be it! The passive moral high ground has gotten us nowhere.

The opening gambit of the book is surprisingly simple: If you were sentenced to five years in prison but had the option of receiving lashes instead, what would you choose? You would probably pick flogging. Wouldn't we all? I propose we give convicts the choice of the lash at the rate of two lashes per year of incarceration. One cannot reasonably argue that merely offering this choice is somehow cruel, especially when the status quo of incarceration remains an option. Prison means losing a part of your life and everything you care for. Compared with this, flogging is just a few very painful strokes on the backside. And it's over in a few minutes. Often, and often very quickly, those who said flogging is too cruel to even consider suddenly say that flogging isn't cruel enough. Personally, I believe that literally ripping skin from the human body is cruel. Even Singapore limits the lash to 24 strokes out of concern for the criminal's survival. Now, flogging may be too harsh, or it may be too soft, but it really can't be both. My defense of flogging -- whipping, caning, lashing, call it what you will -- is meant to be provocative, but only because something extreme is needed to shatter the status quo. We are in denial about the brutality of the uniquely American invention of mass incarceration. In 1970, before the war on drugs and a plethora of get-tough laws increased sentence lengths and the number of nonviolent offenders in prison, 338,000 Americans were incarcerated. There was even hope that prisons would simply fade into the dustbin of history. That didn't happen. From 1970 to 1990, crime rose while we locked up a million more people. Since then we've locked up another million and crime has gone down. In truth there is very little correlation between incarceration and the crime rate. Is there something so special about that second million behind bars? Were they the only ones who were "real criminals"? Did we simply get it wrong with the first 1.3 million we locked up? If so, should we let them out? America now has more prisoners, 2.3 million, than any other country in the world. Ever. Our rate of incarceration is roughly seven times that of Canada or any Western European country. Stalin, at the height of the Soviet gulag, had fewer prisoners than America does now (although admittedly the chances of living through American incarceration are quite a bit higher). We deem it necessary to incarcerate more of our people -- in rate as well as absolute numbers -- than the world's most draconian authoritarian regimes. Think about that. Despite our "land of the free" motto, we have more prisoners than China, and they have a billion more people than we do. If 2.3-million prisoners doesn't sound like a lot, let me put this number in perspective. It's more than the total number of American military personnel -- Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, Coast Guard, Reserves, and National Guard. Even the army of correctional officers needed to guard 2.3-million prisoners outnumbers the U.S. Marines. If we condensed our nationwide penal system into a single city, it would be the fourth-largest city in America, with the population of Baltimore, Boston, and San Francisco combined. When I was a police officer in Baltimore, I don't think anyone I arrested hadn't been arrested before. Even the juveniles I arrested all had records. Because not only does incarceration not "cure" criminality, in many ways it makes it worse. From behind bars, prisoners can't be parents, hold jobs, maintain relationships, or take care of their elders. Their spouse suffers. Their children suffer. And because of this, in the long run, we all suffer. Because one stint in prison so often leads to another, millions have come to alternate between incarceration and freedom while their families and communities suffer the economic, social, and political consequences of their absence. Some time in the past few decades we've lost the concept of justice in a free society. Historically, even though great efforts were made to keep "outsiders" and the "undeserving" poor off public welfare rolls, society's undesirables -- the destitute, the disabled, the insane, and of course criminals -- were still considered part of the community. The proverbial village idiot may have been mocked, beat up, and abused, but there was no doubt he was the village's idiot. Some combination of religious charity, public duty, and family obligation provided (certainly not always adequately) for society's least wanted. Exile was a punishment of last resort, and a severe one at that. To be banished from the community was in some ways the ultimate punishment. And prisons, whether or not this was our intention, brought back banishment and exile, effectively creating a disposable class of people to be locked away and discarded. True evil happens in secret, when the masses of "decent" folks can't or don't want to see it happen. In being, as a contemporary observer aptly described Newgate Prison, New York's first, "unseen from the world," prisons severed the essential link between a community and punishment. Public punishment and shame became isolation and containment. Without being visible, convicts went from being part of us, the greater community, to a more foreign "them." Now we simply wait for them -- the troubled, the unproductive, the unlucky -- to break the law. And then we hold them for months and years, again and again, until they age out of violent crime or die. All this because we've taken a traditional punishment such as flogging out of the arsenal. We've run out of choices, choices desperately needed if we're to have any hope of reducing our incarceration rate by 85 percent, back in line with the rest of free world, back to a level we used to have. So is flogging still too cruel to contemplate? Perhaps it's not as crazy as you thought. And even if you're adamant that flogging is a barbaric, inhumane form of punishment, how can offering criminals the choice of the lash in lieu of incarceration be so bad? If flogging were really worse than prison, nobody would choose it. Of course most people would choose the rattan cane over the prison cell. And that's my point. Faced with the choice between hard time and the lash, the lash is better. What does that say about prison? Peter Moskos is an assistant professor of law, police science, and criminal-justice administration at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and teaches at the City University of New York's doctoral program in sociology and at Laguardia Community College. He is a former Baltimore City police officer and author of Cop in the Hood (Princeton University Press, 2008). His book In Defense of Flogging will be published in June by Basic Books. Copyright 2011. All rights reserved. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

American Politics blog, The Economist, London, 25 April 2011Crime and punishmentA revival of flogging?PETER MOSKOS, a former Baltimore cop and now a professor of law and criminal justice, mounts a defence of flogging as a possible alternative to incarceration:

Mr Moskos adds that he does not expect to see flogging reinstated, and deep down, wouldn't want to. So this is just a thought experiment. And it's worthwhile, as such thought experiments usually are. Flogging would be overtly punitive, as modern incarceration is, but it would abandon the pretense of rehabilitative potential, which incarceration retains. A swift, discrete corporal punishment would also minimise the externalities of prison, which adversely affect the families and communities of the offender. A prisoner cannot hold a job, go to school, or act in a normal caretaking capacity; that disrupts a number of lives, and contributes to the cycle of criminal behaviour. I'm reminded of an old liberal friend here in Austin, who is proud of once having played a "Twelve Angry Men"-style role while serving on a jury. The jury agreed that the offender should be convicted of a moderately-serious felony charge, but at my friend's urging, they declined to impose an additional $10,000 penalty, as the burden of that payment would've fallen on the family, rather than the unemployed convict.

But the "moral justness" of the flogging option, as Mr Moskos articulates it, rests on the fact that flogging would limit such externalities (and that the physical punishment would be presented as an option to the prisoner, rather than to the judge or jury). And so the thought experiment prompts a recognition that we could achieve a similar value through other focused punishments, which avoid the brutality of flogging. Hawaii has gained notice for an innovative programme called Honest Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE), for example. That approach rests on "swift, predictable, and immediate sanctions" for drug offenders, with frequent screenings for drug use and short prison stays, of perhaps a few days, when an offender violates the terms of probation. It has reduced recidivism for such offense by more than 50%. It's hard to extrapolate that outward for more serious crimes; no one would suggest a few days in jail as an appropriate punishment for armed robbery. But front-loading the system with more targeted penalties for minor infractions could reduce the probability of serious violations further down the line, by allowing minor offenders to maintain the opportunities -- for employment, education, and family life -- that help keep people embedded on the right side of the law. |

About this website |

I propose we give convicts the choice of the lash at the rate of two lashes per year of incarceration. One cannot reasonably argue that merely offering this choice is somehow cruel, especially when the status quo of incarceration remains an option. Prison means losing a part of your life and everything you care for. Compared with this, flogging is just a few very painful strokes on the backside...

I propose we give convicts the choice of the lash at the rate of two lashes per year of incarceration. One cannot reasonably argue that merely offering this choice is somehow cruel, especially when the status quo of incarceration remains an option. Prison means losing a part of your life and everything you care for. Compared with this, flogging is just a few very painful strokes on the backside...