BBC News Online, London, 23 November 2006

Bolivia goes back to the whip

By Lucy Ash

Crossing Continents, BBC Radio 4Native American community justice is making a comeback under Bolivia's first indigenous president with the emphasis on the whip.

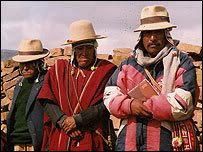

In Wilicala, a remote village in the Andean highland, a group of men were on their way to a meeting. As they walked through the market square I noticed some coloured ropes slung around their chests. The ropes were chicotes or whips and the men wearing them were mallkus -- the word for prince or leader in the Aymara language.

Francisco Espejo, an elderly man whose teeth were stained green from chewing coca leaves, was one of them. He said he was delighted that whipping is now an officially sanctioned punishment.

"When we had attorneys from the Western justice system, they put people behind bars for 20 years," he said. "Those with money bought good lawyers and didn't go to jail so what kind of justice was that?

Certain village elders are equipped with whips to punish offenders

"It's much better to give someone a few lashes and be done with it."

One of President Evo Morales's biggest campaign promises was to revolutionise the justice system. He vowed to promote pre-Columbian community-based courts in which village elders try wrongdoers and determine how they should be punished.

This practice, which predates the Incas, has three main rules which are: Amu Sua -- Don't Steal; Amu Llulla -- Don't Lie, and Ama Quella -- Don't Be Lazy.

Native American law

Most of the mallkus were reluctant to talk to outsiders.

"Some people are still afraid to talk about these things" -- Professor Waskar Ari, Aymara academic

"Community justice was a very secretive practice," explained Waskar Ari, an Aymara Indian and university professor. "When the Bolivian state was controlled by whites they used Western justice as a way of subordinating the Indians and the memory of that is still strong in some parts.

"That is why some people are still afraid to talk about these things."

But under President Morales the underground is going mainstream. Granting traditional justice official status alongside national laws is a vital part of what he calls his "decolonisation" strategy.

There is a new department devoted to Native American law inside the justice ministry and the law faculty of San Andres University in La Paz recently started a three-year community justice course for people from indigenous backgrounds.

The recently appointed head of Bolivia's penal system, Ramiros Llanos, says the old methods are the best way to handle small crimes like the theft of some cattle in a village. Overcrowding in prisons, he adds, has reduced them to "human garbage tips".

Mob fury

A massive backlog of court cases and the snail-like speed of Bolivia's justice system can drive people to desperate acts.

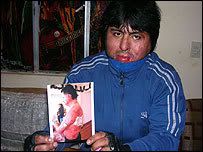

William Villca, lynching survivor

William Villca, a tailor, was nearly killed last summer when he was mistaken for a thief by an angry crowd in the city of Cochabamba. "Suddenly we were surrounded by about 40 people all screaming 'we don't want criminals here! We will burn you, hang you, and kill you!' he said.

"They tied us up and poured petrol all over our clothes. Then they threw lighted matches at us and one landed on my arm."

Today Mr Villca wears a bandage which covers his neck and chin; he has lost one of his earlobes and has trouble moving his fingers. Despite dozens of skin grafts and operations, he can no longer use a sewing machine or hold a pencil.

Cochabamba, the city where Mr Villca was attacked, is notorious for similar incidents, according to human rights lawyer Rose Gloria Acha. "Lynching is a distortion of community justice -- the Indian courts have never sanctioned the death penalty -- but, in their minds, people sometimes make a connection," she says.

"Victims of crime in poor neighbourhoods feel abandoned by the state. They say no police officers will help unless you pay bribes."

Police under pressure

Grover Zapata, a police major in Cochabamba, flatly denies his officers are corrupt.

Grover Zapata, Police major

"We have one policeman for 5,000 citizens and we lack resources," he says. "Sometimes, we ask the public for help with our expenses. It's true sometimes we don't have enough money for petrol to get to the scene of a crime, for example."

The new justice minister, Casimira Rodriguez, says the lynchings were not about community justice but rather a total absence of justice in a country which spends just 1% of its national budget on its judiciary.

A Quechua Indian from the countryside around Cochabamba, the minister spent her teens in virtual slavery as a maid before escaping and founding a domestic workers union. Her own experience of corrupt judges has made her wary of the Western justice system.

The minister described community justice as free, quick and transparent but she said the punishments must be measured and did not fit all crimes. Serious offences like rape or murder, she said, should go through the ordinary system because village courts do not have the resources for fingerprints, and other forensic evidence.

"Both types of justice have to complement each other," she said.

The Washington Times, USA, 29 November 2006

Inca justice system eyed by Morales may use whipping

By Anton Foek

The Washington Times(extract)

THE HAGUE -- Bolivian President Evo Morales, on a state visit to the Netherlands, said he is searching for a new model of democracy that could include reviving the ancient tradition of whipping petty criminals as an alternative to jail.

"When I was a kid I was punished several times, being whipped and lashed," the leftist president said Monday in a speech to an audience of businessmen and government officials from both Bolivia and the Netherlands. "Whenever I did something wrong, I received punishment with a chicote [the loose end of a rope], and always believed that the system our ancestors used was better than the system in the northern justice system. It's much more democratic," he said.

Meanwhile, some 5,000 Indians from across Bolivia converged on La Paz, the capital, yesterday to demand that opposition lawmakers approve a sweeping land reform bill proposed by Mr. Morales. Some demonstrators had walked as far as 300 miles in marches begun several weeks ago from the Andean mountains and plains of Bolivia, culminating in yesterday's rally in the capital. The demonstrators were seeking to put pressure on Mr. Morales' conservative opponents in the Senate who have blocked his proposal to redistribute millions of acres of unproductive land to the country's landless poor.

Mr. Morales, elected with strong backing from his Andean nation's Indian community at the end of last year, promised during the campaign that he would look to traditional practices to make the justice system more equitable.

Several Bolivians attending his address at the Institute for Social Sciences in The Hague said indigenous and traditional community justice was not only sanctioned now in Bolivia, but making a strong comeback. One Morales supporter said Western-trained lawyers and judges in Bolivia put all criminals behind bars for 20 years or more, even if they committed only minor crimes. Defendants who can afford good lawyers, however, generally avoid any punishment at all.

The use of whipping to punish petty crimes in Bolivia dates back to the days of the Incas, when men were known to have walked around carrying colorful ropes in baskets. "During the Inca empire," Mr. Morales said with a broad smile, "a community-based court system led by the village elders punished vandals and other criminals for their wrongdoings and determined how and when they would be punished.

"It mostly ended in a few lashes, like the one I received when I was a kid. They did it for my own good. Look where I am today."

[...]