|

CONTENTS

On this page:

3. Historical background and legislative timeline

On other pages:

1. Introduction

2. Implements and terminology

4. Corporal punishment of "juveniles"

5. "Prison discipline" canings

6. What caning of adults involved

7. What caning of juveniles involved

8. Interesting cases (adult)

9. Interesting cases (juvenile)

10. Statistics

11. Illegal punishments, kangaroo courts, native/customary courts

12. The deterrent effect of corporal punishment

13. The abolition of JCP

3: Historical background and legislative timeline

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

In the early days of the 17th-century Cape Colony, under the rule of the

Dutch East India Company, corporal punishment was usually reserved for those

convicted of petty misdemeanours. Even so, it was not uncommon for whippings of

more than one hundred lashes to be administered, sometimes resulting in serious

injury or even death (H Venter, Die Geskiedenis Van Die Suid Afrikaanse

Gevangenisstelsel: 1652-1958 [History of the South African Prison System], 3 (1959).(1)

After 150 years of Dutch rule under Roman-Dutch law, Britain took power in

the Cape in 1806, and the legal and judicial system began to take on a more

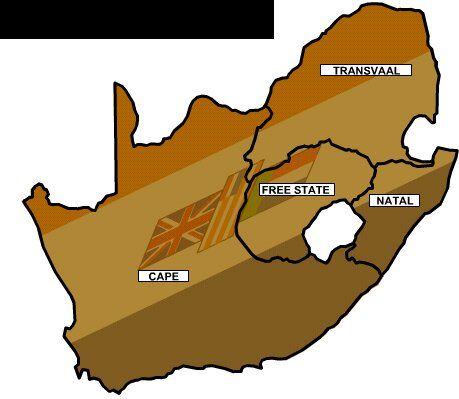

English form. In the 19th century there were four separate jurisdictions: Cape

Colony (aka Cape of Good Hope), Natal, Orange Free State, and the South African

Republic (later Transvaal).

In 1910 these four colonies merged to form the Union of South Africa.

For the next few decades South Africa was in legal terms much like many other parts of the British Empire. But in 1948 the white-supremacist Afrikaner National Party unexpectedly won the general election (in which black people had no vote), heralding nearly half a century of hard-right racist rule. The Dutch-descended Afrikaners threw off the British

yoke –- South Africa left the Commonwealth in 1961 and became a Republic –- and

introduced a much more repressive and authoritarian regime, in which corporal

punishment played a significant role. By 1970 South Africa had become a

quasi-fascist police state. For the next few decades South Africa was in legal terms much like many other parts of the British Empire. But in 1948 the white-supremacist Afrikaner National Party unexpectedly won the general election (in which black people had no vote), heralding nearly half a century of hard-right racist rule. The Dutch-descended Afrikaners threw off the British

yoke –- South Africa left the Commonwealth in 1961 and became a Republic –- and

introduced a much more repressive and authoritarian regime, in which corporal

punishment played a significant role. By 1970 South Africa had become a

quasi-fascist police state.

Because of this, judicial corporal punishment came to be regarded by many anti-apartheid activists, and notably the African National Congress (ANC), as synonymous with the hated Afrikaner regime.

(In fact, this wasn't entirely true. As we shall see, some Africans themselves believed that JCP was often a more appropriate penalty than imprisonment. Nor should it be thought that CP was applied only to non-white offenders.)

It was no great surprise, then, that when universal suffrage at last arrived and the ANC came to power in 1994, the days of CP were numbered. JCP was finally abolished in 1997 (see Section 13).

LEGISLATIVE TIMELINE

1666:

Rules were issued making it an offence to damage a tree on public property. The penalty was "a sound flogging at the foot of the gallows". (2)

1680:

Simon van der Stel, the second Governor of Cape Town, imposed penalties for

illegal hunting. A licence system was introduced. Punishment for infringements

included fines, confiscation of firearms and "corporal punishment", though it is not clear what form this took.(2)

1691:

The Governor issued an Ordinance (C2271 Original Ordinance Book, 19 October

1691) to protect farmers by prohibiting migration beyond the Cape's borders:

"All free peoples outside the boundary posts or borders of the Cape territory and that of Stellenbosch, together with those settled at Drakenstein, or settled round about there with their livestock, should break up their camps as quickly as possible within the next six months, and by

this day have settled themselves within the proper limits with goods and chattels, on pain of corporal punishment as deserters and vagrants, and their house, herds and cattle pens subject to confiscation at their own expense".

1809:

The Hottentot Proclamation (otherwise known as the Caledon code) was

the first of a series of pass laws initiated by the British authorities, who had come to power at the Cape in 1806. It was aimed at helping Afrikaner farmers by controlling the mobility of the labour force. Penalties for breaches by natives included flogging. Pass laws had been in force from as early as 1760. (3)

1818:

Proclamation prescribing a maximum sentence of two months imprisonment and a fine of 25 rixdalers for a defaulting servant, to which corporal punishment could be added for a second and subsequent offence.

(4)

1828:

The Criminal Procedure Act No 40, together with the Evidence Act of 1830, introduced criminal laws substantially modelled on the English system. (5)

The English adversary system, first introduced at the Cape, was later adopted by the other colonies (Orange, Natal, Transvaal). Many of the corporal punishment laws were derived from this legislation.

1828:

Ordinance No 50 repealed the Hottentot Proclamation of 1809 and

"freed the coloured from the pass system and the risk of being flogged for offences against the labour laws".

(4)

1856:

In Cape Colony (Act 20/1856 (C) s.42), up to 36 strokes could be imposed in the event of a second or subsequent conviction within two years, which could be combined with imprisonment.

1858:

The Basic Law of the South African Republic (later Transvaal) was enacted.

Article 149 stated that the whipping of white people was forbidden. (6)

1860:

Legislation enacted in the Cape Colony limited magistrates’ courts from

imposing more than 30 strokes and superior courts more than 50 strokes. This was also the limit in the Transvaal, but in Orange it was only 24 (Lashes

Regulation Ordinance No 7 of 1903 (O)).

1864:

Article 6 of SAR Ordinance No 5 reiterated that corporal punishment was for

non-whites only. It stated that no white person shall be subjected to the

punishment of flogging.(6)

1872:

A Proclamation to control the mobility of the labour force on the mines at

Kimberley provided that any black person was de facto excluded from

owning diamond claims or trading in diamonds and was liable to imprisonment or

corporal punishment if found in the precincts of the camp without a pass signed

by his master or a magistrate.(7)

The Kimberley diamond mines in 1873. From G.F. Williams, The Diamond Mines

of South Africa, New York, 1906. The Kimberley diamond mines in 1873. From G.F. Williams, The Diamond Mines

of South Africa, New York, 1906.

1880:

Legislation was introduced in Transvaal to permit white escaped prisoners to be whipped (Act No 14).(6)

In the same year, the courts in the Cape condemned the practice of deferring a whipping until part of the prison sentence had been served and inflicting it in instalments: R v Nortje [1880] 1 EDC 231.

1888:

Act No 5 (Transvaal) made provision for white offenders to be whipped.

1892:

Act No 21 allowed the courts to impose corporal punishment on white men for

a wide variety of crimes. However, in none of the colonies could a female be

whipped: Act 20/56 Cape s.43, Magistrates Courts Act 22/1896 (N) s.21,

Ord 7/1903 (O) s.5, Magistrates Court Ordinance No 7 of 1902 (O) s.64,

Ord 1 of 1903 (T) s.259).

South African History Online South African History Online

1911:

The Transvaal Supreme Court ruled that a sentence of ten strokes was a very

serious punishment which could be imposed only in exceptional circumstances: R v Kambula [1911] TPD 239.

1917:

The general magistrates' court jurisdiction had remained unchanged in the

Cape since 1856 (Act 20/1856 (C) s.42) -- up to 36 strokes in the event of a

second or subsequent conviction within two years, which could be combined with

imprisonment. In Transvaal, both in his ordinary jurisdiction and on remittal, a magistrate could impose up to 25 strokes for a first conviction for certain

common law crimes and statutory offences. Natal allowed up to 20 strokes with a

cane or rod for a first offence, which could be accompanied by imprisonment,

while the Chief Magistrates of Durban and Pietermaritzburg had the extended

power to impose 25 strokes (Act 22/1896 (N) s.21, Act 32/1905 (N).(8)

However, in 1917 the criminal codes of the four separate colonies were

repealed, and uniformity was achieved throughout the new Union of South Africa

(created in 1910). The 1917 Criminal Procedure and Evidence Act restricted all courts from imposing more than fifteen strokes.

1927:

The Black Administration Act 38/1927 was enacted. S.20(1)(a) provided that the Minister might confer in writing on a Chief or Headman or his deputy the jurisdiction to try and punish any black person for offences at common law or under black law and custom, including stock theft. The sentence could include corporal punishment in the case of unmarried males below the apparent age of 30.

1932:

The Native Service Contract Act was enacted. It was later described

as an "abominable measure that legalised the whipping of African lads under

eighteen for offences against the master and servant laws".(4)

1944:

It was now required that any sentence of adult whipping imposed either by a

Magistrates Court or within a prison be subject to automatic review (Magistrates Court Act 32/1944 s.93). However, the review power did not apply to juvenile punishments, except where the juvenile accused was tried together with another person to whose sentence automatic review did apply.

At the same time the number of strokes which could be imposed by Magistrates

was reduced from fifteen to ten.

In the same Act the Magistrates' power to award the cat-o'-nine tails was

removed -- only the cane could be used. Use of the cat was thus restricted to the Supreme Court.

1945:

The Lansdown Commission (9) was appointed to inquire into penal matters in South Africa. It noted that judicial corporal punishment had been abolished in many Western countries. However, it decided that its continued use in South Africa was justified, in particular because it was regarded by many as a punishment of "special efficacy" for Africans.

It proposed that the maximum number of strokes should be reduced to eight for adults and five for juveniles, and that no person should be whipped on more than two occasions, or not at all if there was evidence that it might cause serious physical or psychological harm (unofficial translation from Afrikaans):

"As regards the number of strokes, although the maximum a magistrate can order is 10 strokes, evidence shows that after six strokes, in the case of a child, and eight, in the case of an adult, the seat becomes numb, so that

further strokes are ineffective [...] (para. 490).(9)

The report also noted that the lash (cat) was rarely ordered, and urged that

it be abolished altogether.

However, the Commission's recommendations fell on stony ground, because a dramatic change of government occurred in 1948.

1952:

The new Afrikaner Nationalist government had come to power in 1948. In 1952

it enacted the Criminal Sentences Amendment Act No 33, which

required the courts to impose, without discretion, a sentence of corporal

punishment, not exceeding ten strokes, on males under 50 convicted of rape

(where the death penalty was not imposed), robbery, housebreaking, and culpable

homicide involving assault with intent to rape or rob. However, the courts were

empowered to suspend the sentence in whole or in part in "special

circumstances". The latter were not clearly defined, and the whole Act was much criticised by the legal profession. One member of the Johannesburg Bar wrote that it was "hastily conceived" and "carelessly drafted".(10)

As another commentator has put it, under this legislation "the courts were

compelled to embark on an orgy of whipping".(1)

The new law came into effect on 16 May 1952 and led immediately to a huge

increase in the use of judicial CP.

In the twenty years between 1942 and 1962, about 1,000,000 strokes were

administered to 180,000 offenders; and 850,000 of these strokes were

administered after the 1952 Act was passed. (Statistics: see Section 10.)

In the year ended 30 June 1963, a total of 17,404 offenders received 83,206

strokes, and in the following year 16,887 offenders received 79,038 strokes,

according to figures given in the House of Assembly by the Minister of Justice.

The comparable figures for 1942 were 2,000 offenders receiving 12,000 strokes.(11)

Although the number of whippings increased eightfold in two decades, this had no apparent effect on the overall crime rate, which continued to rise faster than the increase in population. However, this is partly because the regime kept inventing new offences, especially those associated with its strange theories of racial segregation –- and with the political opposition thereto.

1953:

Section 1 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act No 8 of 1953 provided

that a person convicted of an offence, even a minor one, committed by way of

protest or in support of a campaign against any law could be sentenced to a

whipping not exceeding ten strokes.

Section 2 provided that persons advising, encouraging, inciting, or

assisting, or using language or doing acts calculated to cause persons to commit offences by way of protest against a law or in support of a campaign for the repeal of any law, could likewise be sentenced to a 500-pound fine, a five-year gaol sentence and/or 15 strokes. Imprisonment and whipping were to be imposed automatically for second and subsequent offences.(12)

1954:

The Riotous Assemblies and Criminal Laws Amendment No 15 "introduced

the novel feature of lashes for political crimes compared to the previous policy of banishment" and "marked a significant intensification of direct state

repression against the democratic opposition".(13)

1955:

The list of offences for which corporal punishment was mandatory was

expanded to include motor car theft, the theft of goods from a motor car, and

receiving stolen property (Criminal Procedure and Evidence Amendment Act

No 29). Section 329(2)(a) of the Act, in particular, provided that:

"subject to ss.355, 342, 344(2) and 346 (and s.345 of the Prisons Act) any person other than a person above the age of fifty years convicted of any offence mentioned in Part II of the Third Schedule shall be sentenced to a whipping of not exceeding 10 strokes with or without imprisonment with hard labour" [emphasis added].

Subsection (b) provided that the Minister could add to the offences in the

Schedule, on a resolution of both Houses of Parliament.

In 1955, for the first time, an upper age limit for the corporal punishment

of men convicted of crimes (as opposed to offences against prison

discipline) was fixed at 60.

1957:

The Witchcraft Suppression Act 1957 provided that, in cases where an

accused person was proved by habit or repute to be a witchdoctor or witchfinder, he could be sentenced to imprisonment of not more than twenty years, or to a whipping not exceeding ten strokes, or to both whipping and imprisonment.

1958:

By this time there was considerable antipathy to the compulsory use of the

punishment, and magistrates were particularly dissatisfied about their inability to use their discretion, especially when the circumstances of the offender indicated that whipping was inappropriate.

1959:

The Prisons Act No 8 of 1959 was passed (see section on prison CP). Also, legislation was introduced that somewhat tempered the use of the cane: limits were placed on its imposition for a first offence, adults could not be whipped on more than one occasion within a three-year period, and those sentenced to a statutory minimum imprisonment were exempted. (14)

1960:

The Children’s Act No 33 of 1960 provided in s.32 that a person who

failed to comply with certain requirements under the Act was guilty of an

offence and, if a child, was liable to a moderate whipping as provided in s.345

of the Criminal Procedure Act.

1962:

The Animals Protection Act No 71 of 1962 provided a punishment of

whipping not exceeding six strokes for certain offences against the Act.

1965:

The Minister of Justice inserted a clause in the Criminal Procedure

Amendment Act 1965 by which compulsory whipping was repealed, and discretion over the imposition of corporal punishment was restored to the courts.(1)

The number of caning sentences fell sharply as a result.

1968:

The Dangerous Weapons Act 1968 provided that, where a person above

the age of 18 years was convicted of an offence involving violence to another

person and it had been proved that he or she killed or injured such other person by using a dangerous weapon or a firearm, he or she where the death sentence was not imposed, notwithstanding anything to the contrary in any law [...] in addition to such other punishment may be sentenced to a whipping not exceeding seven strokes.

1976:

The Viljoen Commission, (6) appointed in 1974, issued its report. It was intended to be a thorough review of criminal justice and penal policy in South Africa. Despite evidence given by African witnesses for the retention of corporal punishment on the basis that it was "respected by Africans and was believed to be an effective deterrent", the report recommended its curtailment.

It also suggested that the maximum number of strokes be limited to five, that no offender should be whipped on more than two occasions, that it should be imposed only for offences involving violence or the defiance of lawful authority, that adult offenders over the age of 30 should be exempt, and that juveniles should be caned on the clothed buttocks.

The report noted a submission from the South African Prisons Service that it

"strongly opposed" attempts to reduce the maximum age limit of 50 for corporal

punishment of prisoners for contravening prison rules. The memorandum claimed that serious problems were caused by the aggressiveness and stubbornness of prisoners older than 30 years which could only be deterred by corporal punishment -- in short, prison discipline could be effectively maintained only by thrashing prisoners as old as 50 years. However, Viljoen recommended reducing this maximum age for prison caning to 40.

1976:

The National Parks Act 1976 provided that if the court convicting a

person of killing certain animals found that the contravention was wilful, it

might on a first or subsequent conviction, in addition to any fine or

imprisonment, sentence such person to corporal punishment not exceeding seven

strokes.

1976-1977:

After widespread unrest in the urban African townships of several large

cities, many schoolchildren were brought before the courts and caned for participating in politically motivated activities.(1)

1977:

The Criminal Procedure Act, No 51 of 1977 was the government's response to the Viljoen report. Not all the report’s recommendations were implemented. The Act provided that:

- adult offenders could not be whipped more than two times, or within a period of three years from the last occasion on which they were sentenced to a whipping — s.292(3) (no such restriction applied to juveniles);

- juvenile whippings had henceforth to be inflicted "over the buttocks which must be covered with normal attire" and not, as previously, on the bare buttocks (adults, however, continued to be caned over their bare buttocks);

- females and all adults over the age of thirty were exempt – s.295(1);

- the maximum number of strokes for all courts was reduced to seven (not

five, as recommended by Viljoen) – s.292(2);

- the whipping might be imposed in addition to or as a substitute for any

other punishment to which the offender might otherwise be sentenced –

s.292(1);

- the instrument was a cane only – s.292(2);

- whippings of adults could be imposed only for robbery, rape, breaking

and entering, theft of motor vehicles, receiving stolen property, gross

indecency between males, attempts to commit the above crimes, culpable

homicide, or statutory offences which imposed the punishment – s.293;

- whippings ordered by a Magistrates Court, other than juvenile

whippings, were subject in the ordinary course to review by a judge –

s.302(1)(a)(iii);

- such whippings should not be inflicted until the review was completed –

s.308;

- persons subject to a whipping but not imprisonment, if not given bail,

had to be held in custody until completion of the review –- s.308(2);

- whippings could not be imposed where the conviction resulted from

certain psychological conditions of the offender –- s.295(2).

However, by virtue of s.36(7) of the Prisons Act, where corporal

punishment had been ordered in more than one sentence passed at or at

approximately the same time on the same person, that punishment was required

to be inflicted at one and the same time and the number of strokes could

total ten -- the remainder of the strokes, if any, were to lapse.

1978:

In Transkei, a supposedly "independent" republic to which a degree of legislative power had been devolved from central government, the authorities proposed a law that would permit female juveniles who had been involved in political activities to be whipped (The Guardian, London, 3 June 1978).

1986:

An amendment to the Criminal Procedure Act provided that an adult

could not be sentenced to a whipping in addition to imprisonment unless the

whole or part of the imprisonment was suspended. This was intended to provide an alternative to prison, thereby alleviating overcrowding in prisons.

In a further amendment to s.293, the number and type of offences for which an offender might be sentenced to an adult whipping was extended to include

sedition, arson, public violence and malicious damage to property, although

bestiality and homosexual acts were removed from the list. The stage was thus

set for an increase in court-imposed whippings in retaliation for

political activity. The new list of corporally punishable offences was intended to deal with offences against public order in the ongoing climate of political unrest.

In Whippings: The Courts, the Legislature and the Unrest (South

African Journal of Human Rights, 1985), Angela Roberts and Julia Sloth-Nielsen

observed that it was

"difficult to understand how offenders involved in unrest-related actions

would distinguish between the informal use of physical violence currently

employed by the police, using quirts, truncheons and sjamboks, and the

formalised physical pain that will now be meted out to them by the courts".

1989:

In Transkei, legislation provided for the corporal punishment of female, as

well as male, offenders. In S v V en 'n Ander [1989] 1 SA 532 (A) Mitchell J observed that the whipping of females was frequently applied by the various magisterial districts of Transkei.

1993:

Corporal punishment for offences against prison discipline was abolished by an amendment to the Correctional Services Act.

1995:

In S v Williams and Others [PDF] (Alternative link) [1995] 3 SA 632 the Constitutional Court of South Africa heard a reference from the Supreme Court following sentences of whipping imposed on six

boys in 1994. [PDF] (Alternative link) [1995] 3 SA 632 the Constitutional Court of South Africa heard a reference from the Supreme Court following sentences of whipping imposed on six

boys in 1994.

The Court found that the provisions of s.294 of the Act (the "juvenile" whipping clauses) violated the Constitution and should be struck down. (see Section 13, The abolition of JCP.)

This landmark case thus brought about the end of judicial corporal punishment for juveniles in South Africa -- although it took some months for the decision to percolate down to all local courts.(14)

1996:

The Correctional Services Amendment Act 79 of 1996 deleted the

provisions in the Prisons Act laying down rules for corporal punishment in prisons for whatever purpose.

1997:

Judicial corporal punishment in South Africa was definitively abolished in all respects with the passing of the Abolition of Corporal Punishment Act 1997 [PDF], which received Presidential assent on 5 September 1997 (Government Gazette 18256). It provided in Section 1 that any law which authorised corporal punishment by a court of law, including a court of traditional leaders, was repealed to the extent that it authorised such punishment, and specific legislative provisions providing for corporal punishment were abolished in the Schedule. [PDF], which received Presidential assent on 5 September 1997 (Government Gazette 18256). It provided in Section 1 that any law which authorised corporal punishment by a court of law, including a court of traditional leaders, was repealed to the extent that it authorised such punishment, and specific legislative provisions providing for corporal punishment were abolished in the Schedule.

FOOTNOTES

(1) James O. Midgley, "Corporal Punishment and Penal Policy", 1982 J. Crim. L. & Criminology Vol. 73 No 1.

(2) John A. Pringle, The Conservationists and the Killers , Bulpin, Cape Town, c.1982. , Bulpin, Cape Town, c.1982.

(3) Jouni Maho, Select Chronology of South African Legislation, Göteborg University, 1997-2002.

(4) Jack Simons and Ray E. Simons, Class and Colour in South Africa 1850-1950 , Penguin African Library 1969. , Penguin African Library 1969.

(5) John Dugard, South African Criminal Law & Procedure, Juta, Cape Town, 1977, p.253.

(6) Verslag van die Kommissie van Ondersoek na die Strafstelsel van die Republiek van Suid-Afrika [Report of the Commission of Enquiry into the Penal System of the Republic of South Africa] ("Viljoen Report"), Government Printer, Pretoria, 1976.

(7) Leonard Thompson, A History of South Africa, Yale University Press, 1990, p.118.

(8) Ellison Khan, "Crime and Punishment 1910-1960", in Acta Juridica 1960, Cape Town, 1961.

(9) Verslag van de Kommissie op Straf- en Gevangenishervorming [Report of the Commission on Penal and Prison Reform] ("Lansdown Report"), Government Printer, Pretoria, 1947.

(10) R.F. Ascham, "The Whipping Act", 1954 SALJ Vol. LXXI, p.145 ff.

(11) Brian Bunting, The Rise of the South African Reich , Penguin Africa Library, 1969. , Penguin Africa Library, 1969.

(12) Eileen Riley, Major Political Events in South Africa, Facts on File, Oxford and New York, 1991, p.36.

(13) Paul B Rich, State Power and Black Politics in South Africa 1912-1951, Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1996.

(14) "Child whipping hasn't stopped", Mail & Guardian, Johannesburg, 25 August 1995.

Next: Section 4: Corporal punishment of "juveniles" Next: Section 4: Corporal punishment of "juveniles"

|

![]()