Corpun file 25229 at www.corpun.com

Plainview Daily Herald, Texas, 1 April 2014

Reader's Page

Please don't tell Daddy

By Louise Hooper Harper

Plainview HeraldWhile pondering my October 2014 birthday -- in numbers I'll be 90 years old -- I suddenly started sifting through some of my unique memories. Old memories are sometimes similar to aged Kodak pictures that have faded and identities of those in the photos have been forgotten.

With nearly nine decades of memories behind me, some are sad and grief-filled, some minor regrets. But many are contented and happy.

Today's column will focus on my freshman year in Anton High School at age 14. If my timing and memory are correct, the day was April 1, 1938, April Fool's Day.

Several in my class, including my first cousin (who in my eyes and opinion thought she could do no wrong). She was among those planning to skip afternoon classes that day.

This memory is not a "Sentimental Journey" since I judge myself on making a youthful mistake: blaming my class mates' encouragement.

Louise Harper

At noon, five or six girl classmates left the high school building, walked through downtown Anton, then to the railroad station on the highway heading east to Lubbock or west to Littlefield. We voted to aim east, making the six miles to Round Up, a little place with a grocery and gas store and then return to Anton before school was dismissed. Few cars and trucks were on the highway in the late 1930s, so, when we heard an engine or saw a vehicle, we ran and hid in the deep bar ditches beside the highway.

One of the teachers came looking for us, found us in a ditch and took us back to school and discipline.

We were given a choice for our punishment by the school's principal. We could stay in several days at noon (without lunch) or get a paddling with a ruler on our stretched out hands. (Only the boys got spanked on their bottoms.)

I did not tell my mother why I failed to walk home for lunch a couple of days.

My brother, 18 months younger than I am but in the same grade, decided he needed to tattletale on his older sister. My first day of punishment I stayed in school study hall and didn't go home for lunch. Zade then tells Mother "why."

Saturday morning mother informed me she was going to report to daddy what I had done. Daddy worked at the Reese Air Force Base in Lubbock so it would be over an hour before he left Lubbock and arrived at home in Anton.

My family was among the "poor people." 1938 was only six years after the Great Depression and some family friends had given us their shabby old sofa after they purchased a new one.

That Saturday I spent lying on the sofa, whining, crying and faking sickness, begging Mother not to tell Daddy. "Please Mother, don't tell Daddy!"

Daddy, who rode to and from work in a car pool, arrived home with his old tin lunch box in his hand and saw me on the sofa. "Hi Sister," he said.

Soon Mother told Daddy about my crime of playing hooky with several other girls on April Fool's Day and were caught and were being punished by the school principal.

Daddy asked me "What is your punishment?" I whined and said, "We could decide between two punishments: spend a week on lunch break in study hall preparing our next lessons or get a spanking on our hands with a wooden ruler." I choose to stay in study hall.

Daddy decided my fate in one short sentence. "Sister, you go back to school Monday and take the hand spanking with a ruler."

I obeyed Daddy!

The principal took my right hand in his left, held it palm up, bent it backward and hit my small tender outstretched hand with the force of his adult male strength -- several times.

From the year 1938 to the 2014, 76 years have gone by and I can still almost feel how bad that hurt! This memory of an April Fool's Day playing hooky from school is not included in my "sentimental journeys." However, I judged myself: I made a wrong youthful decision and never ever did I do that again!

(Louise Hooper Harper is a Plainview freelance writer.)

© 2014 MyPlainview.com. All rights reserved.

Corpun file 25307 at www.corpun.com

The Nation, New York, 8 April 2014

Why Are Black Students Facing Corporal Punishment in Public Schools?

By Sarah Carr

Lexington, Miss. -- Students in this central Mississippi town quickly learn that even seemingly minor transgressions can bring down the weight of the paddle. Seventh grader Steven Burns recounts getting smacked with it for wearing the wrong color shirt; Jacoby Blue, 12, for failing to finish her homework on time; and Curtis Hill, 16, for defiantly throwing a crumpled piece of paper in the trash can.

In Holmes County, where 99 percent of the public school children are black, students say corporal punishment traditionally starts at daycare and Head Start centers, where teachers rap preschool-age students lightly with rulers and pencils, cautioning: "Just wait until you get to big school."

At "big school," the wooden paddle is larger -- the employee handbook calls for it to be up to thirty inches long, half an inch thick, and from two to three inches wide -- and the teachers sometimes admonish errant students to "talk to the wood or go to the hood" (slang for choosing between the paddle and an out-of-school suspension).

"It's not really about you learning to listen, it's about you feeling pain," says Kameisha Smith, a 19-year-old college student who attended public schools in Holmes County and is helping to organize a student-led resistance to the practice.

In recent months, school districts have come under heavy criticism for suspending and expelling black students at much higher rates than white ones, starting in the youngest grades. During the 2011-12 school year, for example, black children made up only 18 percent of the preschool students included in one national survey, yet nearly half of the preschoolers suspended multiple times.

"We must tackle these brutal truths head-on," said Education Secretary Arne Duncan during a January press conference at which he issued new federal guidelines for school discipline. The guidelines call for schools to reduce their reliance on suspensions, through such strategies as improved training for staff members and partnerships with community groups and juvenile justice organizations.

Yet both the guidelines and the national conversation have overlooked the brutal truths when it comes to physical discipline in the schools, which still occurs tens of thousands of times a year. As with suspensions, black children are far more likely to get paddled at school than white ones. In 2012, for instance, black children made up 18 percent of the student population but 35 percent of reported incidents of corporal punishment in states that allow the practice, according to a survey from the Education Department's Office for Civil Rights.

In Mississippi, where about half of all public school students are black, these racial gaps have widened slightly in recent years: in 2012, black children accounted for about 64 percent of those paddled, up from 60 percent in 2000.

The national conversation over corporal punishment is muted partly because schoolhouse paddling is limited predominantly to one region: the South. Only nineteen states (including just a few in the West and Midwest) permit the practice, while students can (and do) get suspended in all states.

But there are other, more complicated reasons that the debate over paddling has taken a different course. In communities like Lexington, the wielders of the paddle and its most vocal defenders are mostly black. Critiques of the practice have become conflated with attacks on the black community's right to self-governance, even when those critiques are voiced by other African-Americans. It's one of the ironies of the debate that defenders speak of corporal punishment in terms of black self-sufficiency -- emphasizing a community's right to determine how it educates its children -- while critics speak of it in terms of black subjugation.

"We feel as if we know what is best for our kids," says Troy Henry, an African-American board member of St. Augustine High School in New Orleans, who three years ago fought against an effort to abolish corporal punishment at the all-male and historically black Catholic school. He added that the paddle helps enforce the importance of rules and boundaries. "The margin for error is much smaller in black communities, especially for black boys," he says.

But Joyce Parker, the African-American founder of a community organization in Greenville, Mississippi, that is opposed to corporal punishment, says the paddle symbolizes a "legacy we're trying to outlive."

"During slavery, we were whipped on the back, beat on the back and dehumanized," she says. "The sad part is that we are doing it ... to ourselves now."

Signs of Change

Even in Mississippi, where a higher percentage of students get physically disciplined than in any other state, the paddle is starting to lose some of its might. The number of beatings fell 33 percent between 2008 and 2012, according to a report by the Clarion-Ledger newspaper in Jackson.

In Holmes County, where Lexington is located, 83 percent of the residents are black; the median household income is about $22,000; and the average life expectancy -- 66 for men and 73.5 for women -- is the lowest of any county in the United States.

Holmes County's nine public schools enroll about 3,000 students. School staffers paddled students 351 times during the 2012-13 school year, according to state figures provided in response to a public records request. That number has fluctuated in recent years, dropping from more than 300 incidents in 2009 to sixty-eight in 2011-12, and bouncing back up in the last school year.

Holmes is not an anomaly, but the prevalence of the practice varies widely throughout the state. In 2012-13, three dozen Mississippi districts reported more cases of corporal punishment than Holmes County, with a few large districts paddling their students more than 1,000 times. Other districts are bowing to criticism and using the paddle less. A few, including Jackson Public Schools in the state's capital, have banned the practice altogether. The recruitment of younger teachers through alternative programs like Teach for America has contributed to the decline, because they are far less likely to embrace corporal punishment.

Like many small towns in the region, Lexington has a rich history and an enduring charm. B.B. King briefly lived here as a young adult, and jazz bassist Malachi Favors and blues musician Lonnie Pitchford were both born here. The commercial center is shaped like a square, as in the famed college town of Oxford 110 miles to the north, with businesses ringing the picturesque courthouse in the center.

On one weekday afternoon in winter, however, a busker carrying a placard with the word cash appeared to be the only sign of life in the square. She tried to attract customers to a small storefront advertising payday loans and title advances. Given the dearth of people, the busker might as well have been addressing her vigorous shouts and motions to the wind.

Debate over the issue of corporal punishment has pitted parents against kids, neighbors against neighbors, and superintendents against principals in some instances. But opponents of corporal punishment have never gained enough traction to eliminate the practice districtwide. (In Mississippi, the decision about whether to paddle is left up to individual communities.)

Defenders of the practice in Holmes argue that corporal punishment is not only a rite of passage and an effective discipline tool, but mandated by the biblical proverb "Spare the rod, spoil the child." They also claim there's a disproportionate need for the paddle in a place where poor children of color will be afforded few breaks down the road if they don't learn to follow the "rules" early on.

Anthony Anderson, a minister and member of the Holmes County Board of Education, says students who learn the importance of "rules and regulations" will be less likely to get into trouble -- or act out violently -- as adults.

"There was no other alternative given in the Bible," he adds.

"Reasonable and Moderate"

Students at Lexington's Nollie Jenkins Family Center, which hosts different afterschool workshops, are pushing back hard against this ethos. They believe the opposite to be true, arguing that paddling is an act of violence that simply begets more violence.

As part of a grassroots campaign, the students are collecting signatures, lobbying school board members and spreading word of their dissent via social media. They face an uphill battle, since a majority of the school board supports the paddle.

Kameisha Smith, who attends Tougaloo College in Jackson, says she was paddled three times between the ages of 10 and 14 as a student in Holmes County public schools. One time, everyone in her class received the punishment for laughing and snickering when they were supposed to be standing silently in line. A second time, a teacher was disappointed with her work. She can't recall the reason for the third paddling.

Students at the county's career and technical school have traditionally been responsible for designing and building the paddles that will be used on their peers (and, occasionally, on themselves). Some of the paddles have names scrawled on them by students or staff. A retired paddle kept at Nollie Jenkins Family Center, for instance, goes by the name "Mr. Feel Good."

It's most common to get paddled on the rear, according to several students at the family center. Typically, students are told to bend forward and place their hands on a desk or wall before the paddle is administered. The district's employee handbook states that only a principal, assistant principal or "designee" can wield the paddle; for children in grades seven and above, the staff member must be the same gender as the student. The handbook also states that "corporal punishment shall be reasonable and moderate" and should be preceded by "less stringent" measures such as counseling. It does not specify how many times a child can be struck or on what part of the body.

But students complain that teachers sometimes stray from both the letter and the spirit of the regulations: administering the paddle without permission of the principal, failing to find a female staff member to paddle older girls, or adding embellishments -- holes in the wood, wrapping two paddles together with tape -- that make the blows hurt more. Occasionally, they say, students get injured, particularly if a student gets hit on the hand.

Three years ago in Mississippi's Tate County, in the northwest part of the state, a 15-year-old's family sued the district, alleging that the teen fainted and pitched forward while being paddled, shattering five teeth and breaking his jaw. (Last year, a judge dismissed the family's federal claims, citing, among other reasons, a Supreme Court ruling that the Eighth Amendment prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment does not apply in school corporal punishment cases.) Similar lawsuits crop up every few years. Mississippi law states that teachers and administrators cannot be held liable in such suits if they follow school district rules and act without "malicious purpose."

Curtis Hill, 16, vividly remembers "Big Daddy," the two paddles wrapped together that a teacher used on students' hands and bottoms when Hill was in the fourth grade. He also remembers the fractured wrist he says one student suffered as a result of a paddling in middle school.

Yet Hill says his family members continue to support corporal punishment. "My mom, my granddaddy, my aunt, they like it because the preacher said -- "

"Spare the rod, spoil the child!" one of his classmates interjects.

In Hill's view, though, the paddle is mostly about "belittling" children. "It makes you feel like nothing," he says.

Powell Rucker, the superintendent of Holmes County schools, says it's rare for school staff to stray from the district rules when it comes to administering the paddle. "I have not seen that frequently," he says, adding that staff members who deviate are disciplined. Rucker says administrators do not routinely hit students on their hands, but that sometimes students stick their hands in front of their bottoms at the last minute, which can cause increased pain. "With the paddles being as small as they are, there have been no major injuries," he says.

For Rucker, who physically disciplined his own children, paddling is a religious imperative. "You can't change the Bible," he says. "You just can't."

"The Way You Were Brought Up"

In addition to citing the Bible and the need to teach children boundaries, defenders of corporal punishment often cite the paddle's crucial role in their own upbringing. "You can't easily dismiss the way you were brought up," says Nathaniel Christian, a minister in Holmes County, who has conflicted feelings about corporal punishment.

Many parents in the county accept paddling as a kind of cultural legacy that should be passed on to their own children. Families who don't want their children to be paddled in school can sign a form exempting them -- an option that some 20 percent of families choose, according to Rucker.

Some parents, however, say they have felt pressured into condoning the paddle. Otherwise, school officials will call them repeatedly, interrupting them at work, and issue suspension after suspension to their children.

Mary Pickett, the parent of a first and a second grader, says she disapproves of corporal punishment because it does little to address the root causes of a child's misbehavior. She signed the form forbidding the paddling of her children. Not long after, she received a call from her son's teacher, who said he was "hollering" and that Pickett needed to come pick him up. Arriving at the school, Pickett says administrators tried to "push the issue," telling her they wouldn't have to call her so much if she allowed them to use the paddle. "I told the principal, 'If I allow it, they will beat the hell out of them every day,'" she recalls.

Rucker says that parents who won't permit paddling and dislike out-of-school suspensions should be willing to come in and sit with their children if they're constantly interrupting other students' learning time. "In order to have some means of control, educators are forced to contact parents" in some cases, he says. Rucker adds that district staff members usually do not call parents without provocation.

LaShunkeita Clark, another parent, thought she had decided against corporal punishment and signed the form prohibiting school staffers from striking her 13-year-old daughter. But while she was serving as a substitute teacher at her daughter's school one day, she realized how hard it is to break from tradition. Her daughter, Ayana, began "cutting up" and misbehaving in front of her mother and other students. Feeling disrespected and embarrassed, Clark's first instinct was to resort to physical discipline. So she allowed an administrator to strike her daughter that day.

In some Mississippi communities, newcomers who find the idea of paddling children abhorrent can feel pressured to accept the practice. Eight years ago, during Robyn Gulley's first week teaching second grade in Sunflower as a Teach for America corps member in the Delta, her mentor rapped disobedient students with a ruler and encouraged Gulley to do the same. Gulley, who is white and grew up in Colorado, tried to find alternative ways to reprimand students. She hung a paper clip with each child's name on it, for instance, and moved down the clips of troublesome students.

Yet when she called the parents of students with chronic behavior problems, they often responded: "Whup 'em -- you just need to wear 'em out." And when she brought unruly students to the principal's office, the administrator told her, "Well, you need to paddle them." Eventually, she stopped taking students to the office and dealt with the problems as best she could on her own. But Gulley continued to worry that spurning the paddle would be construed as disrespectful. She was one of only a few white teachers in the school; most of her colleagues were experienced educators who had grown up in the community. "If I didn't do it, the implication was that I thought I was better than them," Gulley recalls.

During her second year of teaching, Gulley paddled students twice. (The district permitted teachers to paddle students in the main office as long as two witnesses were present, Gulley says.) The first time, she struck a younger student who constantly jumped out of her seat and made rude, taunting comments to classmates. The second time, Gulley paddled students who had been involved in a fight, but only after the principal challenged her to do so.

Gulley, who now teaches at a charter school in New Orleans, says she met several wonderful parents who physically disciplined their children. But she questions the efficacy of the strategy. "The feeling after you paddle a child is terrible," she says. "You are angry. They are angry. And I do not think it is effective. It's especially not effective for a white person doing it to a black child in an all-black community."

Seeking Alternatives to the Paddle

Even some adamant supporters of corporal punishment, like Rucker, do not believe that paddling always works. For some students, Rucker thinks that better counseling and social services are needed.

"But we can't afford it," he says, adding that the school receives only enough funding to provide one counselor for every 500 students.

Opponents of corporal punishment say they recognize that they have to present effective alternatives if they hope to change minds. "Something has to go in its place," says Smith, the college student. She and others at the Nollie Jenkins Family Center have been trying to promote peer mediation, in which students step in to counsel one another through crises and conflicts.

The many ways that corporal punishment has become embedded not only in schools, but in homes and hearts, can make it complicated to attack the practice on the grounds of racial disparity -- especially in communities where black leaders and parents may view that attack as an encroachment on their civil rights, not as an enhancement of their children's. Those who view the paddle partly as preparation for the hard challenges that many poor black children will face in the world as teenagers and adults are not always disposed to regard its banishment as an advance in racial justice.

"There's a whole part of corporal punishment that's a reflection of American society, of who we are and where we came from," says Gulley. "In a lot of ways, we're stuck."

Corpun file 25429 at www.corpun.com

WUFT News (University of Florida NPR/PBS), Gainesville, 14 April 2014

Concerns Raised About Corporal Punishment in North Central Florida Schools

By Perri Konecky

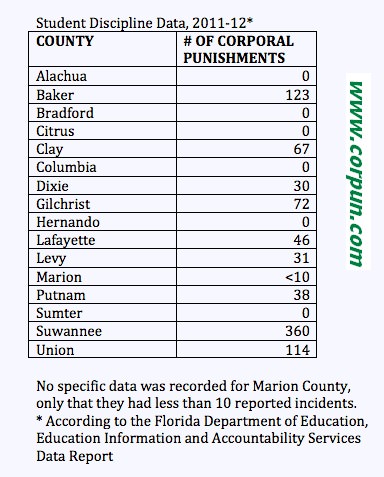

More students get paddled in the Suwannee County School District than anywhere else in Florida.

That highest ranking comes even though Suwannee is one of the least populated counties in the state. Out of the 67 counties in Florida, only 28 reported using corporal punishment during the 2011-12 academic year.

According to Tiffany Cowie, spokeswoman for the Florida Department of Education, Suwannee reported 359 students received corporal punishment during the 2012-13 school year.

Corporal punishment is still a routine practice in public schools throughout the United States. [No, it isn't. In many places in the north it has been unknown for many years. -- C.F.] There are 19 states that still engage in this form of penalty.

According to the Florida Department of Education Student Information Database, during the 2011-12 school year, 360 students received corporal punishment in the Suwannee County School District.

When asked about the county's high number of corporal punishment incidents, Suwannee School District Superintendent Jerry Scarborough declined to comment.

"We have a serious problem here and it needs to be scrutinized," said James McNulty, founder of Floridians Against Corporal Punishment in Public School.

As a civil rights and human rights activist, McNulty has recently made corporal punishment in Suwannee County the next mission of his campaign. He has already had success in Santa Rosa County. He said he is ready to focus on this county because of the alarming numbers of reported incidents.

McNulty's passion for the movement is undeniable.

"It is in Florida's public schools, of which I am a product of, that I first learned to hate, to fear, to hold contempt, to have feelings of rage and revenge," he said. "Public school is where I also learned what violence was."

The Suwannee County School District student code of conduct for the 2013-14 school year defines corporal punishment as "the moderate use of paddling in front of a certified adult witness by a principal/administrator may be necessary to maintain discipline or to enforce school rules."

Although the code of conduct includes a permission form for parents to check yes or no to using the punishment on their children, there are many unanswered questions about the practices.

McNulty said the code of conduct does not specify the measurements of the instrument being used to hit the student, how many hits are being administered, what specific actions warrant corporal punishment, if there are gender restrictions (males hitting young females) and more.

"You will find that virtually anything goes," McNulty said.

McNulty's first pursuit was in Santa Rosa County, where months of opposition ended with a victory. According to the Northwest Florida Daily News, school officials will abolish corporal punishment, also known as "paddling", in the student code of conduct for the 2014-15 school year.

He recalls the tedious process that went on for many months; endless public record requests, ignored emails and phone calls, and frenzied school board meetings. McNulty's determination and perseverance marked a milestone in Santa Rosa County, but only a minor accomplishment in his civil rights campaign.

McNulty first became involved when he was at work and overheard two parents discussing school officials calling them for approval to paddle their teenage high school daughters.

Marie Caton, a parent of a Santa Rosa County student, initially said yes and gave permission to use corporal punishment on her 10-year-old son. It was after seeing "the deepest shade of black and purple" on her son's body when the guilt ensued for giving permission, she said.

"These people are paid and hired by the state to protect our children, not physically hurt them," Caton said. "As educated people you'd think they could come up with something better than punishment with a board."

McNulty is currently awaiting requested public records of the recent school year for Suwannee County.

However, eliminating the use of corporal punishment does not alleviate the problem of student misbehavior.

"The use of out of school suspension should not be increased due to a reduction in the use of corporal punishment," said Joseph Gagnon, association professor in special education at the University of Florida. "To do so, would be to replace one ineffective method of intervention with another ineffective method."

Last year, Gagnon was approached by the Southern Poverty Law Center and teamed up with Professor Brianna Kennedy-Lewis to conduct the study "Disciplinary Practices in Florida Schools."

According to the study, corporal punishment models and teaches that violence is an effective approach to solving problems. It also said paddling only punishes misbehavior and doesn't teach positive social behavior.

After surveying Title I school principals, Gagnon noted these schools haven't implemented policies that "prevent problem behavior and promote appropriate behavior."

The intensive study offers recommendations concerning the use of corporal punishment starting with the immediate abolition of corporal punishment in Florida schools.

According to the study, individualized intervention and positive behavior intervention and support are shown to promote social and emotional learning for students.

He recommends "ongoing professional development to help educators, school staff and administrators implement evidence-based alternatives to corporal punishment and other ineffectual punishments."

"We think we're so advanced in the United States, but South Africa outlawed corporal punishment 20 years ago," Gagnon said. "We're not always ahead of the curve."

Corpun file 25244 at www.corpun.com

St Louis Post-Dispatch, Missouri, 16 April 2014

No spanking in schools across Missouri under lawmaker's proposal

By Alex Stuckey

JEFFERSON CITY -- Through 13 years of teaching, Jennifer Kavanaugh never dreamed of hitting a child -- not even once.

Kavanaugh, now a fifth-grade teacher at St. Margaret of Scotland School in St. Louis, previously taught in a school where children were physically punished for bad behavior, but she never participated.

She knows there are teachers across the state who do, however, and she wants it stopped.

"All studies point to the fact that corporal punishment does not make for a more peaceful, happier child," she said at the Capitol on Wednesday.

Kavanaugh and about 30 of her fifth-grade students attended a hearing Wednesday on a bill, sponsored by Sen. Joe Keaveny, D-St. Louis, that would ban corporal punishment, or spanking, in both public and private schools in the state. The Senate Committee on Progress and Development unanimously passed the bill Wednesday afternoon.

"We need to stop assaulting our kids," Keaveny said.

Missouri is one of 19 states that still allows corporal punishment in schools. The most recent states to ban it were New Mexico, in 2011, and Ohio, in 2009. Illinois also has a ban on this form of discipline, according to the Center for Effective Discipline, a National Child Protection Training Center program.

The country's patchwork laws can largely be attributed to a 1977 Supreme Court ruling that left the issue up to the states. In Ingraham v. Wright, Florida students argued that the state's corporal punishment policy violated both their Eighth and 14th Amendment rights. The court upheld Florida's policy.

In Missouri, the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education requires each school district's written discipline policy to include a policy on corporal punishment. Should it be used, the local school board must determine how it will be used and whether a parent will be notified or can opt for a different form of discipline.

The department does not keep track of which districts in the state use corporal punishment. However, in 2009 the Missouri School Boards' Association estimated that at least 70 of the more than 500 districts in the state had policies allowing the use of corporal punishment.

A Post-Dispatch inquiry found that many districts in the St. Louis area -- including St. Louis, Clayton, Lindbergh and Riverview Gardens -- do not allow this type of discipline.

Ferguson-Florissant's disciplinary policy also does not include spanking. District officials believe there are better ways -- ranging from parent-teacher conferences to suspension or expulsion -- to discipline a child, district spokeswoman Jana Shortt said.

But some districts do allow the practice. About 4,200 students across the state were physically punished in the 2009-2010 school year, the most recent numbers available, according to the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.

The Fox School District in Jefferson County used to allow spanking in its schools, but it changed its policy in the early 2000s, said Lorenzo Rizzi, the district's assistant superintendent of secondary education.

"I think the Board of Education no longer sees it as a proper way to punish kids," Rizzi said. "The use of physical response doesn't change behavior -- oftentimes it escalates."

The trend away from corporal punishment mirrors a national trend. For the 2009-2010 school year, about 184,500 students were physically punished, compared with about 223,000 in the 2005-2006 school year, according to the department.

A decrease, however, is not enough for Kavanaugh. She wants to see teachers use positive behavior supports.

"We need to require more of teachers," she said.

No one spoke against the bill at Wednesday's hearing. However, Sen. Gina Walsh, D-Bellefontaine Neighbors, voiced concern about including private schools in the bill.

"I do not support corporal punishment, but my parents sent me to a faith-based school ... I'm opposed to government interfering in the curriculum."

Senate Minority Leader and committee Chairwoman Jolie Justus, D-Kansas City, said she wanted to move the bill forward but believed there could be a hang-up on the private school portion.

"I suspect we'll hear from people who don't want state intervention in private schools," Justus said.

"At some point, we may need some compromise when some folks come and talk to us. Right now, I haven't heard any opposition."

Follow-up: 24 April 2014 - Missouri lawmakers debate ban on corporal punishment in schools (with video clip)

Corpun file 25267 at www.corpun.com

Ocala Star-Banner, Florida, 22 April 2014

School Board votes to ban paddling

By Joe Callahan

Staff WriterThe Marion County School Board on Tuesday unexpectedly voted to remove corporal punishment from the 2014-15 student code of conduct, just a year after it was added back as a disciplinary option.

The reversal was led by School Board member Ron Crawford, who last year cast the swing vote to re-establish corporal punishment after a three-year absence. On Tuesday, Crawford said he had to listen to his constituents.

Crawford asked that the words "corporal punishment" be removed from the 2014-15 code of student conduct, stating he has received only negative comments from parents after the district reinstated it last April.

"I have never seen such a (negative) response in all the years I have been on the board," said Crawford, adding that everywhere he goes, he hears: "What were you thinking?"

School Board member Ron Crawford, shown in this June 11, 2013 file photo, urged that corporal punishment be removed from School District policies.

Bruce Ackerman/Star-Banner

While Crawford said he has been bombarded by parents criticizing him for last year's decision, board member Carol Ely said she has received only positive comments.

Last year, Ely, a retired principal, led the charge to re-establish paddling, stating that it should be at least an option for school-based administrators.

By a 3-2 vote, the board ruled last year that paddling could only be used if a parent gives a standing written permission once a year. In addition, the principal must obtain verbal permission at the time the punishment is handed down.

Under the 2013-14 policy, corporal punishment can only be used at the elementary school level. It can only be used on a child once a semester. Principals are not bound to use the punishment. With Tuesday's 3-2 vote, corporal punishment ends June 30. Ely and board member Nancy Stacy both supported keeping paddling in the code of conduct.

Crawford said that ever since paddling was re-established last year, against the wishes of Superintendent of Schools George Tomyn, it has rarely, if ever, has been used utilized at any of the schools.

Crawford has said Tomyn has encouraged principals not to paddle out of fear the district could be sued. Since it is not being used, Crawford said there is no point in keeping it in.

The 2014-15 student code of conduct also includes for the first time a section on cyberbullying.

The cyberbullying addition will keep the district in line with new state requirements passed last spring. It will go into effect on July 1.

The new cyberbullying policy is required under state statute 1006.147. The state policy was created last spring, just weeks after the School Board had already approved the 2013-14 code of conduct. That's why it had to be added now for the 2014-15 school year.

Cyberbullying is addressed in the current 2013-14 conduct code, but not by name and only vaguely under the "bullying and harassment" section.

"We (as a district) put a lot of work into this code of conduct," said School Board Co-Chairman Angie Boynton. School officials said adding cyberbullying separately will give school administrators more direction in foiling online bullies.

The new state statute, which is now officially in the 2014-15 code of conduct, gives administrators more leverage in addressing cyberbullies.

Until the new language was added, cyberbullying was difficult to address because the actions often happen off campus and the student is conducting the behavior at home.

The new statute and district policy better defines the violations and therefore gives school districts more ability to address the actions.

Besides typical texting and Facebook threats, the policy also specifies that students can be in violation of cyberbullying for creating a Web page targeting a student.

The district policy states that a student would be in violation if an electronic threat, insult or "dehumanizing gesture is severe or pervasive enough to create an intimidating, hostile or offensive educational environment."

Mark Vianello, executive director of student services, said last month the new policy will allow the district to issue punishment even if the act of cyberbullying occurred from a computer located off campus.

But that would be the case only if the threat deters a student from participating in school activities.

For a student who is found to have committed a first-time bullying offense, the punishment can range from a warning to a 10-day suspension.

A student who is caught for a second time must sign an anti-bullying contract. Depending on the severity of the second offense, the student could get another warning, up to a 10-day suspension, or be placed in an alternative school.

The third offense would mean the student violated the anti-bullying contract and would be sent to an alternative school.

Copyright © 2014 Ocala.com. All rights reserved.

Corpun file 25268 at www.corpun.com

wgem.com (WGEM-TV), Quincy, Illinois, 24 April 2014

Missouri lawmakers debate ban on corporal punishment in schools

By Jeremy Culver

Multimedia Journalist

PALMYRA, Mo. (WGEM) - Missouri is one of 19 states that still allows corporal punishment in schools, but lawmakers may soon change that.Right now each school district in Missouri decides its own corporal punishment policy. According to the Missouri School Board about 70 districts in the state still allow the use of corporal punishment. The board does not show if the schools practice the measure or not.

Palmyra school district banned the practice in 2011. Superintendent Eric Churchwell believes each district should continue to make its own policy.

"That was our board's decision," Churchwell said. "If the state just bans it altogether, you're taking that freedom from an individual school district or that local control. There may be communities that it is highly effective and it does work."

Churchwell says when he first got to Palmyra corporal punishment was allowed in the school, but was rarely practiced before it was banned in 2011.

Parent Stacey Conrad says she also believes it should be left as a district issue.

"Every district knows its students and its constituents better than the entire state," Conrad said. "What works in a rural area may not work in an urban area and what works in an urban area may not work in a rural area either. I really think that school districts need to have the autonomy to decide what's best for their students."

Conrad says schools need a variety of options to enforce the rules in place, but she feels letting a school decide on the matter is better than outright banning the issue.

Clark County Middle School allows corporal punishment. Principal Jason Church says they only allow corporal punishment per parent request and consent. It is only used about three to four times a year. Church says students knowing it could be used helps keep them from acting out in school.

All content © Copyright 2000 - 2014 WorldNow and WGEM. All Rights Reserved.

Follow-up: 16 May 2014 - How some major legislation fared in the Missouri General Assembly: Did not pass

About this website

Search this site

Article: American school paddling

Other external links: US school CP

Archive 2014: USA

Video clips

Picture index

Previous month

Following month